The Fat of Fed Beasts Read online

Page 2

One of the men shouted again and pointed his semi-automatic pistol at roughly the point where my head had been before I knelt, and then lay down, and I thought the old man was going to get shot. I recall thinking it would be a shame and something of a waste and a tragedy for a person to get shot just because he was deaf and maybe didn’t have the best peripheral vision. I reached out my right hand. From where I was lying, face down on the linoleum, I could just touch the old man’s foot. He was wearing brogues in thick, tan leather with the depth of shine that I knew, from having watched my father clean his shoes, and mine and, later, D’s, every Sunday evening until I was fourteen years old, came only as a result of repeated polishing over many years. I pinched the turn-up of his right trouser leg between my first and second fingers – I could not quite reach it with my thumb to get a better grip – and tugged, as best I could, to attract his attention and alert him to the danger he was in. He lifted his foot without turning, and shook it, as if shooing away a fly. When he put it down again, the heel – which I noticed was rubber, although the shoe had a leather half sole which was nearly new, or at least not worn – landed heavily on the first two joints of my index and middle fingers, and I could not help shouting out, even though I was trying not to, on account of not wanting to attract the attention of the men with guns, and possibly get shot.

When I shouted the old man, who was evidently not deaf, turned, and at the same time bent down towards me. It is still also possible that he was deaf, and, feeling something under his heel – a pen, or even a wallet, perhaps – had turned and simultaneously bent down to see what it was that he might be stepping on. Whether it was the sound of me shouting or the sensation of obstruction, or some combination of the two, he turned and bent at precisely the moment when the man with the gun pulled the trigger. I thought it was likely that the old man still hadn’t realised what was going on around him and I closed my eyes, involuntarily.

Here I lay the page I’ve just finished face down on the pile to my right and, before picking the next page from the larger pile in front of me, I take a moment to point out that although I am a trained observer, I was not on duty. Even if I had been, I would not have seen everything because the decision to close my eyes was not conscious; it would not have been a dereliction of duty, even if I had been on duty, officially, because my unconscious mind anticipated the horror and traumatic images it would not be able to eradicate easily and took over control from my trained, conscious mind, despite the training, and I doubt that, honestly, any of you would have done any differently. Theo, perhaps, could have kept his eyes open; but not you, D, and not Alex.

After which I continue.

When he turned around I saw that I had allowed myself, from the stoop and the slowness in moving forward and perhaps even the idea that he might be deaf or in some way visually impaired, to generate an image in my own mind of a man older than he really was, which was perhaps, I now saw, only mid-sixties, seventy maximum, about the same age my father would have been. I observed this before I closed my eyes and consequently missed the moment when the bullet, as a result of his bending down towards me at the same moment that he turned, missed his face by what could only have been millimetres, judging from the angle of fire I observed when I reopened my eyes, by which time the bullet had passed through a laminated “Cash Withdrawals” sign, through the plaster board and red-painted skim wall to which the sign was affixed, presumably by some sort of industrial polychloroprene adhesive, and through into the office or meeting room or interview room where it must have hit a person I judged from the pitch of the subsequent screams to be a woman, possibly a female bank employee who was in the office or interview room at the time. This woman had not been in the public area of the bank since the entry of the gunmen, and so would obviously not have seen them or heard the instruction to get down on the floor – or, more likely, given the flimsiness of the dividing wall – she may have heard the instruction indistinctly, or may have heard it clearly but simply not understood it or realised that it applied to her, given that she had no visual or other context in which to interpret the instruction as a threat to her own well-being, and was therefore still upright, her head at approximately the same altitude as that of the old (but not ancient) man who I could now see had once been tall but had lost an inch or two to age and gravity, and was thus – the woman – in the (albeit probably deflected) line of fire for no reason other than sheer bad luck/incomprehension.

Jesus, Sis, can we just cut to the chase?

D has a memory stick in his hand. He has been turning it over and over, tapping one end then the other on the thick varnish of the meeting room table. He would have started off trying to listen, I know, albeit not very hard and not for very long. After a while his concentration would have drifted; his eyes would have lost focus and I know that by now he will be timing the gaps between trains, again, counting seconds under his breath. Our meeting room is in a building up by where the railway crosses over into the station. The sound-proofing is good and you can’t really hear the trains through the sealed windows, although you can see the aluminium frames vibrate slightly, if you look, and especially if, as now, there is a fly caught in a web in the top right hand corner of the window. As usual, I have chosen the chair facing the windows. I do this to reduce the potential for distraction in my fellow team members, D especially. While I am confident of my own capacity to concentrate, my brother has always lacked focus; he has always been unable to stay truly present – in a room, or in a conversation – even when it is clearly in his own interest to do so. Right now, he will have given up on my report, and – since Theo has recently confirmed that he will not be with us much longer – D lacks even the primal motivation of not aggravating the boss too much that seems, up to now, to have restrained more overt displays of dissatisfaction and boredom.

D says, I mean, this only happened this morning.

He is speaking to Theo, not to me. Theo says, What is your point, D?

D makes a noise like there is something stuck a long way up his sinuses. He says, My sister can’t go out for a pint of fucking milk without falling over something. She can’t go to the bank like anyone else and get some cash – pay in a cheque, whatever – without running into three armed men and a couple of murders.

I have mentioned only one possible murder so far, and that not conclusive. Theo speaks mildly, in a tone that, whether he knows it or not, is guaranteed to provoke D. I’m certain Theo knows what he is doing.

D says, That’s my point! She’s been reading for, what, eight minutes? EIGHT minutes, and we’re maybe ONE minute into the actual event. It was only this morning. D turns away from Theo, back to face me. When do you even get time to type all this shit?

Theo has taught me not to allow myself to be distracted. I say, The details are important, D. We all know that.

OK, but Jesus, Sis. You’re face down on the lino. Some civilian’s dead and you’re waiting for what I’m assuming here is the subject to get shot in the face. Right? Can you not just tell us: is the old guy in or not?

It is Monday and despite the heat Theo is wearing the herringbone suit. He also has on a white poplin shirt and an anonymous, but possibly regimental, tie with a thin green forty-five degree stripe on a broader red stripe on a darker green background. He has trimmed his beard, which is silver. Not long after D started, Theo took him aside and gave him the name of the tailor who had made this suit; D wrote it down but hadn’t actually visited. Recently D tried calling Theo OMT, short for Old Man Theo. Not to his face, obviously; but in the office, when we were supposed to be working. It was OK in emails or texts, but when you said it aloud even D had to admit it wasn’t that snappy and it hasn’t stuck. Theo would be about the same age as the older man in my report, the man in the bank.

Theo says, Allow Rada to report the incident in her own manner. He always says that. We won’t know what’s important and what isn’t until she has finished. God is in the details.

D knows this; we all know this, but D is still impatient. Can’t we just take it from the point where the old deaf guy gets shot and dies and turns out to be someone we’re interested in? Please, Sis?

I hate it when he calls me Sis, especially at work. He knows this, of course, which is why he does it. We have discussed this, at home, more than once. At work, I always tell him, we should be professional. D generally says that’s a joke, on account of how he’s the one trying to drag the place into the twenty-first century. The memory stick he has been fiddling with contains his position paper on calculating Lifetime Value, which, according to the written agenda Theo circulated at the start of the meeting, D will present when we’re through with the reports. He must know that interrupting, and calling me Sis, is not going to make me get through my report any more quickly. It never has.

Theo nods and I lift a new page up in front of my face and begin reading again.

I saw the man who had fired his gun take his eyes for a moment off the older man who was still standing, who in fact was straightening up from where he had been bending down to look at me. I saw the gunman’s eyes beneath the balaclava helmet; they were grey and looked clouded. The older man must have realised by now that something out of the ordinary and severely threatening to himself and other people was going on, but he did nothing, other than to straighten up. He stood, apparently waiting for the man with the gun to turn back to him and resume his threats. It occurred to me then that perhaps the older man was neither deaf nor visually impaired and might not have been absorbed, in particular, in correctly punching in his Personal Identification Number, but was perhaps more of the absent-minded professor-type with fully working senses that were nonetheless overwhelmed (in terms of neurological stimulation and the kind of messages capable of reaching and attracting the attention of his conscious mind) by the contemplation of some abstruse and potentially world-changing mathematical formula or theorem or whatnot, and that was why he seemed not to have noticed what was going on around him and to get down on the floor like everybody else. But it then occurred to me that if that – the absent-minded professor thing – accounted for the older man’s initial lack of awareness, or response, at least, to what was going on and being said, or shouted, it would not adequately explain why, when he had turned around and could plainly see the man with a gun no more than six feet away from him, and could see the people around him, including me, lying for the most part face down on the floor, and must have heard the shot that had missed his face by no more than millimetres, and could, like the rest of us, hear the continuous or rather pullulating screams emanating from behind the partition wall through which the bullet had passed, why, given all of that, he did nothing but stand and wait. It must have been obvious that he was caught up in a robbery or some kind of siege or even terrorist situation. At this point I had not been able conclusively to dismiss the claim made by one of the men with guns that they were in fact policemen, although none of them had actually shouted Police! or even Armed Police! as their first action on entering the bank with guns in the way that I imagine, on the basis of watching a number of films and TV shows, they would have done if they had in fact been policemen, or at least would have been supposed to do by protocol and legally-enforceable guidance, although I’m pretty sure that in some of the films or TV shows I’ve seen the failure of the police to shout Police! or Armed Police! was the subject of much discussion and dispute amongst the various characters – who often had differing memories and interpretations of the events, not to mention differing motives and interests – and was, in fact, the principal plot-point driving the drama, and it was likely that such dramas were based to some extent on reality and that such an omission might occur also in the excitement of real-life events. It was therefore still possible that the older professorial man might have believed himself to be involved in a robbery or siege or terrorist situation in the process of being interrupted and thwarted by the forces of law and order. But even if this were the case, it still did not explain adequately why, when faced by a man in a balaclava helmet with a gun he was obviously prepared to fire and who had told him to get down on the floor like everybody else, why the older man didn’t, but stood there, apparently oblivious to the gravity of the situation, the only person in the public area of the bank without a gun still upright, waiting for the man who had fired his gun and missed him by millimetres to re-focus his attention, waiting, in fact, for all the world like a professor who has asked his seminar students a fundamental question to which he of course knows the answer, or at least an answer, but has no intention of letting his students off the hook by answering before at least one of them has worked it out for himself. Waiting, in other words, mildly, as if to see what would happen next.

It occurred to me then that the theorem or formula or whatever might not have been important and world-changing but rather otiose and ultimately fruitless, and that the moment when the professor-type guy was withdrawing cash irritatingly slowly, at least to those waiting in the queue behind him, and ignoring the instructions of armed men in a frankly thoughtless way that might just get us all killed, was in fact the precise moment when he realised that the theorem he had been developing was not important and world-changing after all, but was actually otiose and fruitless, and that he had wasted the last five years of his professional, professorial-type life, and that he now faced ridicule and retirement having achieved nothing of substance since his initial, prodigious breakthrough at the age of twenty. In the nihilistic mood this realisation had engendered, he might not care what happened to him and might, in some way, even welcome the possibility of being shot and killed. But such despair did not seem to tally with the expression of mild interest and even curiosity that I had detected on the older man’s features and which I felt was inconsistent with suicidal depression. I will defer to Alex on this point, but my initial assessment was that it was not possible both to wish seriously to be dead and to be curious about what the future might bring, in my opinion.

Alex nods in agreement, but says nothing. As usual, he is sitting across the table from me, not actually looking at me, but at the wall to my left (or my right from his point of view), leaving D and Theo to face each other across the full length of the mahogany oval.

For his part, the man with a gun first turned not to the older man, but to his colleague with the sub-machine gun, a Heckler and Koch UMP45 with flash suppresser and vertical forward hold. Without saying anything, he gestured towards the wall where the bullet hole was clearly visible in the Cash Withdrawal sign, and from behind which the high-pitched screaming continued, albeit with gradually diminishing intensity. The second man moved in the direction that the first had indicated, picking his way between the frightened bodies of those lying on the floor. He was tall and walked with an awkward, high-stepping gait in an attempt to avoid contact with the victims and potential witnesses, but still managed to step on the hair of one woman whom I judged to be in her early thirties. The woman’s hair was long and loose and covered her face and spilled out around it, on the floor. When the gunman stepped on her hair, the woman squealed, then quickly muffled the sound. The man continued towards a door, which was set in the wall some way along from the cash machine at which the older professor-type man and I had been queuing. He tried the door, which was locked and had beside it, set into the wall, a metal plate in something like brushed aluminium with a button and a small grille that was probably an intercom, and a keypad with the usual twelve small buttons in four rows of three, including all the digits from zero to 9, plus C for cancelling entries and either * or # – I could not see which – and which was either redundant and included purely for symmetry, or was to be pressed after the correct numerical code had been entered, depending on the manufacturer (of which I was, at that point, and for obvious reasons, unaware). Confronted with a locked door, from behind which the sound of screaming could still be distinctly heard, the man took his right hand from the trigger and, allowing the shoulder st

rap to bear the weight of the sub-machine gun while he steadied it with his left, drew back his right hand and punched the key pad. This was not a punch in the way that we might normally talk about punching a code into say a telephone, or a cash machine, where there is in fact no actual punching involved but only touching, poking, or at most prodding with a single, usually index, finger. The man was dressed all in black, like the other two, with a balaclava over his face. He had formed a tight fist and hit the keypad precisely, his four larger knuckles landing simultaneously on the 3, 6, 9 and * or # buttons. As the first joint of each finger was held perpendicular to the flat back of his hand, and the second and third joints were curled tightly into the palm and the thumb tucked over out of harm’s way – as, in other words, the gunman had made a perfect flat karate-practitioner’s fist – there was a realistic possibility that the remaining nine buttons were also pressed at precisely the same time. After hitting the keypad twice, he rubbed his knuckles briefly against the biceps of his left arm before trying the door again and finding it still locked.

During this time – probably no more than seventy-five to ninety seconds since the shot had been fired – the probably female person in what was presumably an office or meeting room or perhaps an interview room in which employees discussed the prospects of the bank loaning money to customers, had continued to scream although by now the intensity of the screaming had reduced to the level where it might more accurately be described as wailing, or keening. Even at this level, however, it was obvious that the sound was exacerbating the already considerable level of fear and general anxiety amongst the bank employees and customers lying on the floor in the public area, although not, apparently, that of the older man who, as previously stated, showed no evidence of fear or anxiety but only mild interest bordering on curiosity. I judged that the screaming/wailing was also likely to have increased the tension and stress levels of the men with guns, with the attendant possibility of reduced rationality in decision-making and the consequential increased risk for those of us on the floor. The first man, the man who had fired the shot, now pointed his gun at a woman lying near the door, not the woman with hair over her face which the second man had inadvertently trodden on, but another, older woman with short, neatly cropped hair that tapered to a point at the nape of her neck in a way that I often think looks attractive in women, although usually in younger women than this one, who was wearing a dark blue blouse in some synthetic sweat-inducing fabric with red piping around the collar and cuffs, and a dark blue skirt and flat shoes that my mother might once have described as ‘sensible’ in a way which indicated that she – my mother – would never have been seen dead in them, before she died, and which, together with the blouse and the skirt clearly indicated that the woman was an employee of the bank. The second gunman told her to get up and open the door without doing anything stupid, which she did; and then, not knowing what else to do, she sat and then lay back down on the floor. The second gunman went through the now open door and, seven or eight seconds later, the keening or wailing having increased in intensity until it was, if anything, louder than it had been at the start, even allowing for the fact that the door between the person screaming and the public area of the bank was now open, the screaming was followed by a second gunshot, and silence.

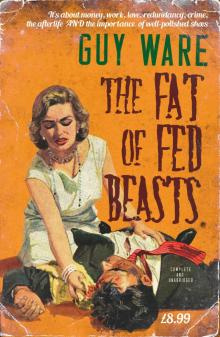

The Fat of Fed Beasts

The Fat of Fed Beasts